Isaac Newton on Learning Mathematical Thinking and Reasoning (Letter from Newton to Hawes)

In this letter - Newton reviews two curricula for school students - while also making his thinking about how learning ideas works better in his experience.

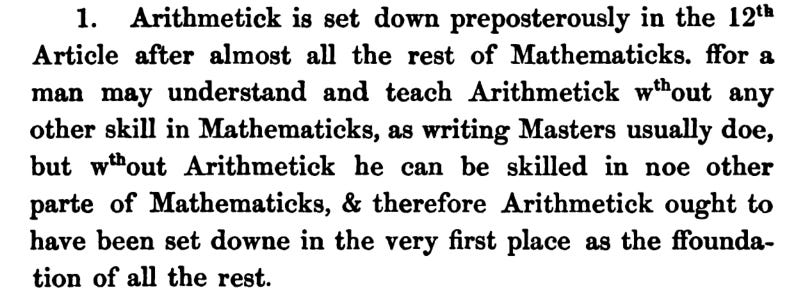

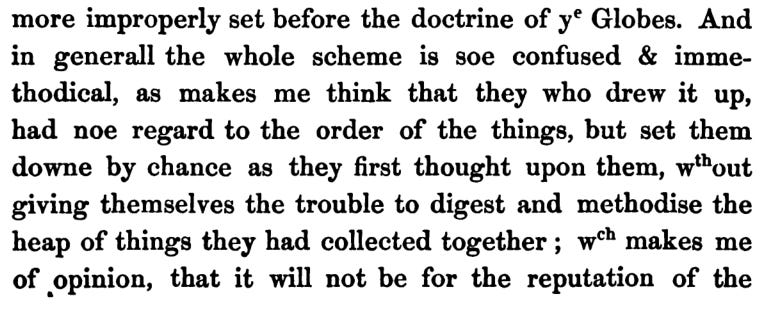

Newton strongly recognized the need for sequencing subjects in a way people can grasp. He found treatments without proper sequence problematic to learn:

Newton cared highly about:

Organization

Digesting material

Presenting in a helpful order

He thoroughly disliked a “heap of things collected together”:

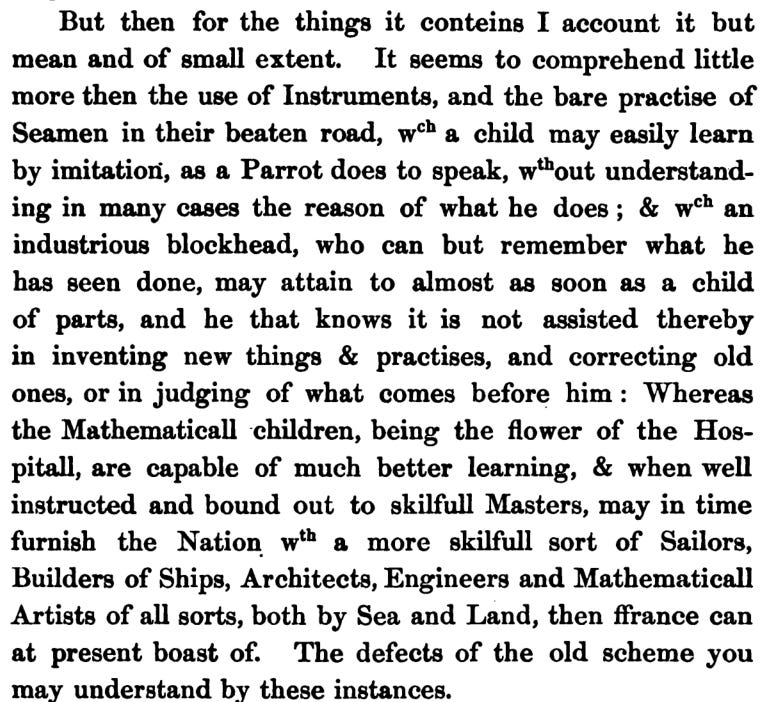

Newton didn’t put much value to rote memorization and the capacity to follow instructions. He talks of “Mathematical children” who are able to invent new things and practices, while also correcting old ones. His main topic of concern was “judgment” about a thing that passes one’s perception.

Here is the same paragraph in more modern language:

Considering what it actually contains, I regard it as mediocre and of little value. It amounts to little more than teaching the use of tools and the rote practices of sailors following well-worn routines—things a child can easily pick up by imitation, like a parrot learning to speak, often without understanding the reasons behind the actions. An industrious fool who can merely remember what he has seen done can acquire this knowledge almost as quickly as a naturally gifted child, yet such training does nothing to help invent new methods, correct old ones, or judge unfamiliar situations. By contrast, mathematically inclined children—the finest pupils of the institution—are capable of far superior learning, and when properly taught and apprenticed to skilled masters, can in time supply the nation with a far more capable class of sailors, shipbuilders, architects, engineers, and mathematical practitioners of every kind, both at sea and on land, surpassing what France can presently boast of. These examples make clear the defects of the old system.

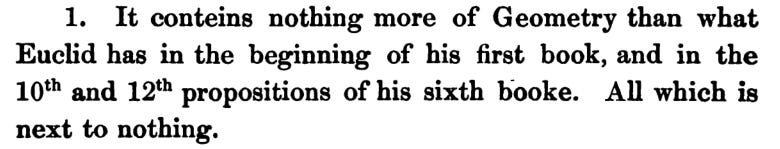

He wanted more of Euclid represented. Euclid’s work span 13 books. But the curriculum builders seem to have ignored most of it:

There is no symbolic stuff - which is needed for anyone trying to invent:

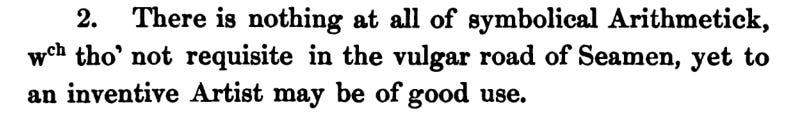

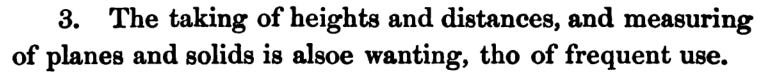

Newton was also a practical man - concerned about practical measurement, sailing, navigation and so on:

Newton was sensitive to order, but also to completeness (or omission):

Newton worried about both the “common sailor” and the “inventive mariner”; he was trying to professionalize the course:

Newton approves of the second version - because it is methodical, short, and complete; those are the things he cared about:

He wanted to include mechanics in the course - because Newton recognized early on that Ship management is a completely mechanical process. We may remember from the Scale book (from the blog series) - even “eminent” engineers - have gotten scaling wrong, and thus sunk ship or lead to their decommissioning. Without mathematical knowledge, refined judgment is impossible in mechanical areas such as ship building:

Next - Newton himself criticizes the idea that intelligence or affinity or knack for or in a particular field - doesn’t allow people to perform at top levels without the necessary mathematical background. Newton very clearly recognizes the need to understand and study the mathematical systematization already done.

Modern version:

It is true that some men, by natural aptitude, have a better knack for mechanical matters than others, and for that reason are sometimes regarded as good mechanics; yet without learning this discipline, they are as far from truly being so as a man with a naturally good geometrical mind who has never learned the principles of geometry is from being a good geometer. For mechanics consists in the doctrine of force and motion, just as geometry consists in that of magnitude and figure; and he who cannot reason about force and motion is as far from being a true mechanic as one who cannot reason about magnitude and figure is from being a geometer.

Now, Newton highlights the difference between those are merely practical and those who are rational - and thus more skilled. First, the merely practical person is not able to find errors in one’s own reasoning, and self-correct. So he becomes stuck. His capability tends to be limited to what he has seen before, or learned to do before via imitation. He is not able to be inventive, find a new way to get something done. So - in Newton’s conception - rational thought is a superset of practical thought. He doesn’t reject practical thought - but points out at its limits and how mathematical thought can overcome those.

Modern version:

A common mechanic can practice what he has been taught or has seen done, but if he makes a mistake, he does not know how to discover it or correct it, and if he is forced off his usual path, he comes to a halt. By contrast, a person who can reason quickly and soundly about form, force, and motion is never at rest until he has overcome every obstacle. Experience is necessary, but there is the same difference between a merely practical mechanic and a rational one as there is between a merely practical surveyor or gauger and a good geometer, or between an empiric in medicine and a learned and rational physician.

Newton also encourages mathematical reasoning due to its generality - it just creates highly skilled people in the force.

Modern version:

Therefore, let it be considered how thoroughly mechanical the structure of a ship is, and upon how many different forces and motions its entire operation and management depend. Then let it be further considered whether it is truly to the advantage of maritime affairs that even our most capable sailors should be nothing more than empirical navigators, or whether they should also be able to reason well about the forms, forces, and motions with which they are constantly engaged. The same argument applies, to a large extent, to many other mechanical occupations, such as shipbuilding, architecture, fortification, and engineering, given the importance of mechanical skill in all of them.

Newton also invokes how Archimedes defended his city in ancient times. And how french engineers are able to superior reasoning skill.

The importance of mechanical skill in such professions can be seen both in the advantage it once gave Archimedes in defending his city against the Romans—by which he made himself famous for all future ages—and in the advantage the French presently hold over all other nations in the quality of their engineers. For it was through mastery of this discipline that Archimedes defended his city. And although French engineers fall short of that great mechanic, by coming closer to him than our own craftsmen do, we can see how effectively they fortify and defend their cities, and how readily they overpower and conquer those of their enemies. You may also consider to what level of excellence that nation has recently raised its naval strength through its schools for sea officers, even in spite of natural disadvantages; and yet your own school is capable of surpassing them, for whereas they rely on a mixture of abilities of every kind, your children are the best talents selected from a great multitude.

Newton valued an attitude of mental flexibility, focused on learning, and free to receive all impressions:

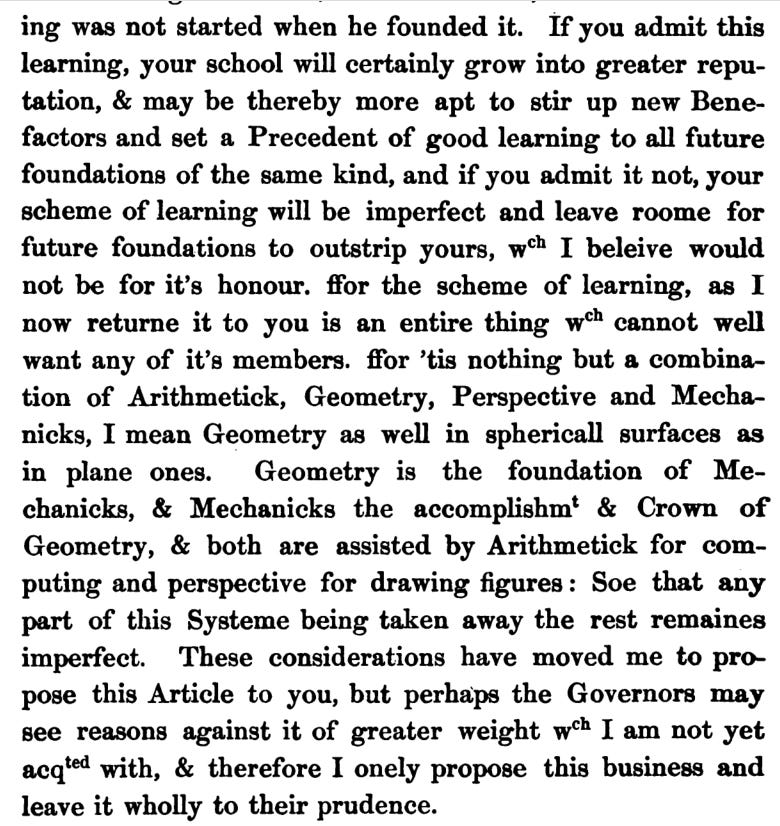

Geometry is the foundation of Mechanics; and Mechanics the accomplishment of Geometry. Arithmetic helps with computing, and Perspective for drawing figures. All of these are inter-related subjects and strengthen the practice of one another:

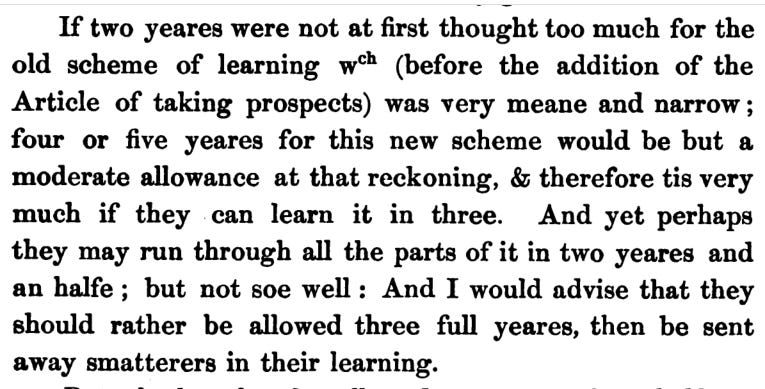

Newton preferred allocating sufficient time to perfect learning - rather than save some time to acquire an imperfect understanding:

Newton also exhibits his practical side here - on how to make the Teacher’s position reputable and attractive to candidates:

Nor do I see how the character and method of the school, in carrying students through the full course of mathematical study, can be conducted so steadily and advantageously unless the mathematics master has certainty about the number of students and the time by which he is expected to prepare them. As matters now stand, you allow a poor mathematics master the freedom to make excuses whenever he proves negligent, while discouraging a good one through uncertainty about his work, his methods, and the recognition and reputation that come from bringing his students to proficiency. You also leave him exposed to the whims of those who may wish, by such means, to take opportunities to harm him in his livelihood or reputation. Whereas it is in your interest to make the position as desirable as possible, so that when it becomes vacant you may have a wider choice of the most suitable candidates, and to encourage them to carry out their duties with confidence and good spirit.

Newton works through some PR side of things - bringing out the administrator within him:

And if it serves the credit and interest of the foundation not only that the boys be well educated, but also that they be placed with the best masters, then appointing two formal occasions each year to examine five boys at a time and bind them out as apprentices may attract a wider and better selection of capable masters than the small, informal examinations now in use—just as a fair attracts more merchants than a minor market. Public notice of these occasions would also make the process more formal and more widely known throughout the nation, thereby contributing to the honor of the foundation and likely encouraging new benefactors. I therefore think that the combination of so many advantages well deserves to be established, unless there is some serious objection to it of which I am not yet aware. For you have told me that once the boys have completed their course of study, there is no danger that they will fail to meet suitable masters at the next public examination, and if any of them should happen not to secure a master then, they would always remain free afterward to go with whatever masters they might find. As for the examinations themselves, I believe that the more public they are, the more the school will be concerned for its reputation, and the greater the reputation it will gain through the good performance of the boys.

As is expected of him - Newton pushes for a study of Euclid (at least 8 of 13 books of the series):

I approve of the plan to have certain Latin authors read in the school, because the best mathematical books are written in that language, and by training the boys in mathematical Latin they will be able to understand them. Synopsis Algebraica and Ward’s Trigonometry are well chosen, and so is Euclides nova methodo, given the short amount of time allowed to the boys. Yet Euclid himself (in Barrow’s edition, I assume) would benefit them more if it could be completed within the time, and would be more useful to them later when reading other authors. Therefore, the governors may decide, if they think fit, that the boys read either Euclides nova methodo or else, at the discretion of the mathematical master, the first six books of Euclid’s Elements in Barrow’s edition for plane geometry, and the eleventh and twelfth books for solids. In this way, the mathematical master will be free to teach the Elements themselves as soon as he finds that he can complete them, along with the rest of the curriculum, within the allotted time. As for the doctrine of the sphere, the first book of Mercator’s Astronomy is brief and well suited to the needs of the school, and may therefore be prescribed.

Newton quotes a mathematician Willliam Oughtred - who asked sailors to collect accurate data on navigation and send to back to mathematicians to improve the science of navigation. Newton adds that - instead of sending voyage data to the Mathematicians, send Mathematicians to the sea voyage - which is a stronger recommendation:

Having now given you my own opinion on these matters, I will also give you that of Mr. Oughtred, a man whose judgment—if anyone’s—may safely be relied upon. For in his book on the circles of proportion, at the end of his discussion of navigation (page 184), he offers this exhortation to seamen: that if the masters of ships and pilots would take the trouble to keep careful and faithful journals of their voyages, setting down in separate columns not only the course they sail, the ship’s progress measured in degrees, and observations of latitude and compass variation, but also their conjectures and reasoning behind the corrections they make for observed errors; together with the qualities and condition of their ship, the varying seasons and directions of the winds, and the hidden motions or disturbances of the seas—when they begin, how long they last, how far they extend, and with what irregularity—and whatever else at sea deserves careful notice, and would then freely share these observations with practitioners truly skilled in mathematics and devoted to the pursuit of truth, then in due time many necessary principles would be brought to light, tending to the improvement of navigation and to the help and safety of those whose callings compel them to entrust their lives and property on the vast ocean to the providence of God. Thus far the very sound and judicious Mr. Oughtred. I would add that if, instead of merely sending the observations of seamen to capable mathematicians on land, the land were to send capable mathematicians to sea, it would contribute far more to the improvement of navigation and to the safety of men’s lives and estates upon that element.

With that point, Newton closes his letter. Overall - that sounded like an extremely helpful letter written to the recipient - considering theoretical, pragmatic, political, administrative, business, psychological and many other aspects of setting up a curriculum for Sailor students. He wrote with these in 1694. I’d think, even today, not many in the field would be able to speak about the subject with such clarity and authority.