Scale (by Geoffrey West) - Part 20

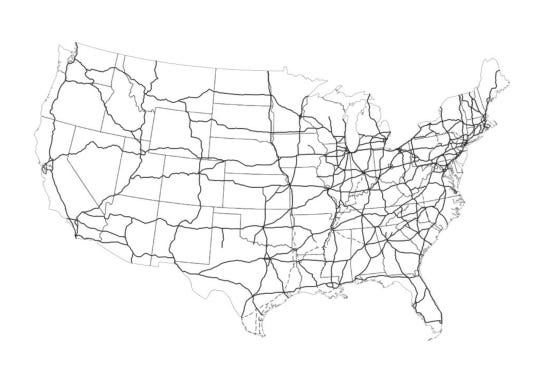

In the USA - an interstate highway system was built. On the surface of it - it looks like a Euclidean project, straight lines, rectangular shapes. At the surface - that judgment looks true.

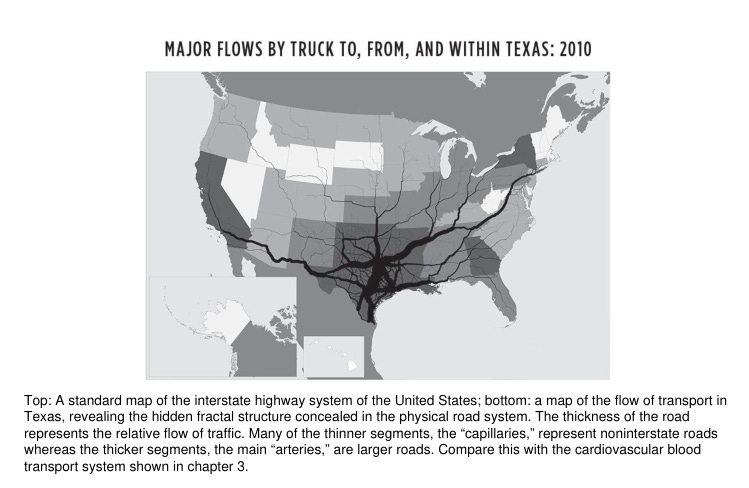

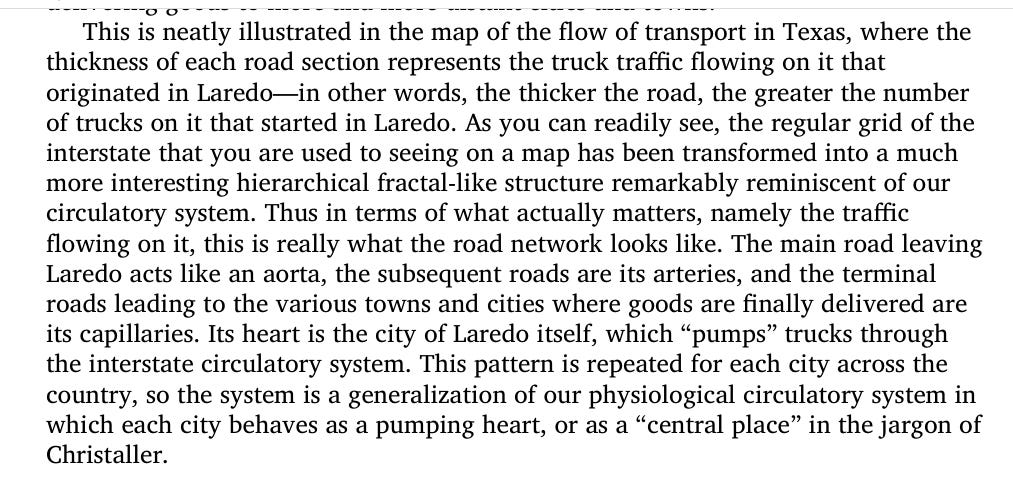

But digging deeper - if we look at the traffic - which is the more important part of assessing the behavior of a road network - what we see is no Euclidean traffic - but rather fractal traffic volume. The traffic moves from the “centers” to the “units” via a “branching” sort of pattern - like we see in the human body.

Each city acts like a heart; the heart pumps blood onto all the surrounding organs, whereas the city pumps resources:

Mike Batty - the author of “The New Science of Cities” - is one of the strongest advocates for building “fractal cities”:

The deployment of the “network concepts” for understanding complex adaptive systems is called “network science” and there are many participants in this area now:

What is the core idea behind “6 degrees of separation”

Pick two people:

1. Just yourself

2. Any random person in “the country” (the USA)

Consider the relation “A knows B”.

Make a graph of all the people you know (1 to many), then further out, all the people known to the people you know and so on.

The core question is - on average - how many “hops” are needed between you and the arbitrarily picked random person?

The USA has 350 million people. Perhaps the number of hops required is quite large -- 50? 100?

Turns out, the actual average “social graph distance” between me and a random person in the USA is just 6. That’s it.

The social world is highly inter-related. I guess the people in business community understand why networks are so important. You can reach pretty much anyone - if you follow the chain, and follow the links available to you.

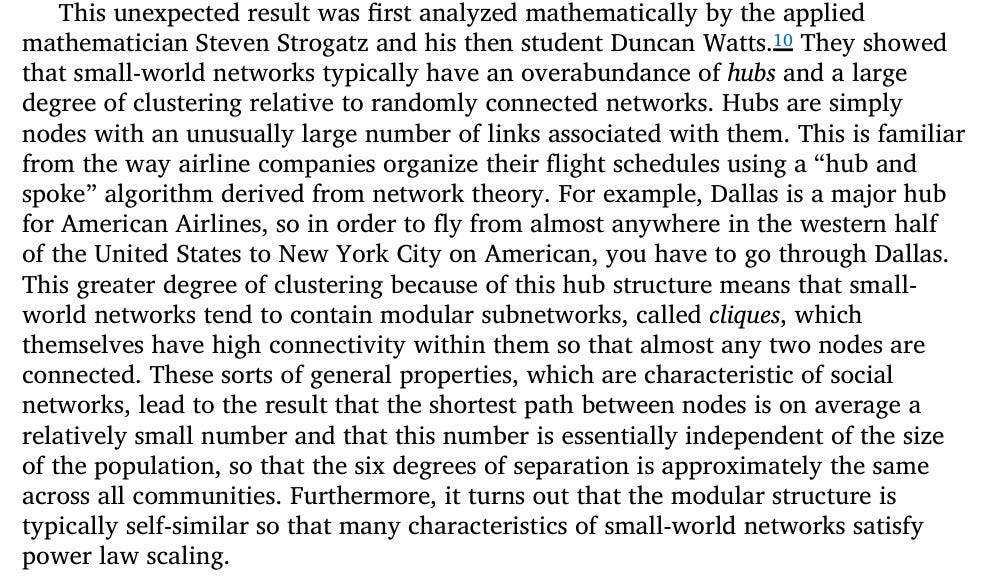

Steven Strogatz gave a mathematical structure to this problem, and was able to find out the deeper reason for this kind of result. The larger graph for a country is made up of small “cliques” or “communities” or “hubs”. There are “small world networks” or “subnetworks” which get connected to the larger whole. That is the main reason behind the number 6:

Here’s a picture of clique/subunit formation:

In London a bridge design was proposed by Arup and Norman Foster - and once constructed was claimed to be an engineering marvel, etc.:

Turns out the bridge was unsafe, and lead to an unexpected amount of resonance and sway; it had to be closed down for 1.5 years to fix the design flaws:

We teach the idea of resonance during school - but the idea was not applied or considered sufficiently during the bridge design:

Clearly - the architects and engineers were highly qualified, experienced and capable and fully aware of resonance. Still, they missed something.

In bridge construction tradition - apparently, people consider vertical motions - but they don’t consider horizontal motion. The cost of the bridge was $30 million. Took them 25% - that is $8 million more plus 1.5 year closure to fix the issue

One of the deep point of this scale book is this: Tradition is good and useful, heuristics are great - but without a systemic Scientific framework to perform validations - tradition can lead you to make big blunders. Tradition and experience can speed up work - but never a substitute for having and deploying scientific models for validating designs.

Milgram - apart from his (in)famous “obedience experiments” and “social distance calculation/proposal” - developed a deeper theory of how the individual becomes highly influenced by the social environment around oneself:

Note: One can find the PDF for “The Experience of Living in Cities by Milgram” here.

The first thing Milgram notes is the psychological harshness of cities; nobody seems to even acknowledge each other, despite the possibilities. People are so disengaged, they may not even report a crime or intervene to help. And of course the casual disregard for one another, fighting with one another for a cab ride or a seat or whatever - people are generally mean to each other in bigger cities:

A great contrast - in a big city like New York no possession left unguarded is safe for even a few days; whereas in a small town there is no such thing - you can leave stuff unattended and come back to find things untouched:

One potential explanation to this sort of antisocial behavior in bigger cities - is overstimulation of our sensory apparatus - forcing us to shut down - because we cannot process anymore and function:

The city offers extremes - of connection, but also depression; of wealth creation, but also higher crime, and so on. For every positive in the city, there is an equally appalling negative: